The debate on industrial offshoring, reshoring, and reindustrialization is on the table. The recent COVID 19 pandemic, the digital transformation, and the need to fight climate change favor new industrialization based on a more sustainable, digital, and innovative model. This is precisely what the European Commission was proposing to the European Parliament and the member states as far back as January 2014.

This article reviews the causes that led to relocation to understand this phenomenon, the reasons that now facilitate the reverse movement of relocation, and the levers that can drive the growth of the Spanish industrial sector.

Contents

Glossary of terms and acronyms

Four Asian Tigers: South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan

BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China & South Africa

EU: European Union

ITO: International Trade Organization

UNCTAD: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

EU4: Enlargement of the EU from 2005.

Industry 4.0: Fourth Industrial Revolution

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

FDI: Foreign Direct Investment

Introduction

We must first understand the importance of the industry for the national economy. The turnover of the Spanish industry reflected by the National Statistics Institute in 2019 amounted to 681,318 million euros in 2019, with a growth of 1.6% compared to the previous year. However, the distribution within the territory is not homogeneous and there are four outstanding communities: Catalonia with 22%, Andalusia with 12%, Madrid with 10.7%, and the Valencian Community with 10% of total sales.

This represents 14% of the total employment level without taking into account the “carryover effect”: A job in the industry supports between 0.5 and 2 jobs in the rest of the productive sectors.

In addition, industrial companies have a more qualified and stable staff obtaining remunerations 16% higher than the average. These better working conditions are not detrimental to business competitiveness, rather labor productivity is 42% higher in the industrial sector than in the economy as a whole.

Manufacturing capacity is also important in the country’s export capacity, generating a positive impact on the trade balance since 33% of sales are destined abroad (22% to the EU and 11% outside the EU).

Unfortunately, the industry continues to lose weight in the Spanish economy and now only represents 16.3% of the Gross Added Value (the main component of GDP) in 2020, compared to 20.7% in 2000 or similar figures. to 40% of the 70s, thus moving away from the objective set by the European Commission in 2014 that the industrial sector accounted for 20% of GDP in 2020.

Thus, not only has this goal not been reached, but the pushback causes the feeling that yet another train has been let through. Even so, this situation must be put into context since this continuous decrease is typical of mature economies that are slowly increasing the weight of the services sector to the detriment of the rest, alongside with the reality of the pandemic that has affected the industrial sector and has not yet has returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Although the natural tendency is true, there are clear opportunities for reindustrialization both at the European and Spanish levels.

Industrial offshoring

In recent decades, Western countries have experienced a strong process of offshoring, this being understood as that by which a company located in any country decides to abandon its activity partially or totally to produce it in different countries.

The first relocation occurred at the end of the 1980s to the so-called “Four Asian Tigers” due to their rapid industrial development. The following waves were the successive enlargements of the EU with the incorporation of Eastern European countries and the appearance on the scene of emerging countries, with China as the main reference.

At a global level, due to their economic, geopolitical, and coordination importance, these emerging countries were the so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), but in the particular case of the European Union, the countries of the enlargement would have to be considered from 2005 (mainly the Visegrád Group: Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia) and, in the case of Spain, to Latin America.

The main cause was the search for competitiveness through lower costs (salaries and raw materials) and proximity to these emerging markets. But there have also been certain factors that have favored this phenomenon, such as the progress of international economic integration thanks to the reduction of trade barriers, the liberalization of internal markets, and the development of information and communication technologies (ICT).

This phenomenon of industrial offshoring opened an intense debate throughout the Western world precisely because of the direct consequences of the increase in unemployment. Even today the term globalization has negative connotations for our population as it is associated with job losses.

Industrial offshoring in Spain

The Spanish case has certain differences to the rest of European countries. In the first place, most companies (84%) have less than 10 employees, a figure much lower than the European average. Companies with more than 250 employees account for 39% of employment and 62% of turnover. And they are mostly multinationals (MNCs) with foreign capital which, as we will see later, have been more likely to relocate. And not only that, but they are also those that represent advanced manufacturing, which is where the loss of employment has mainly focused on traditional and intermediate companies, which are the ones that make up the Spanish industrial fabric.

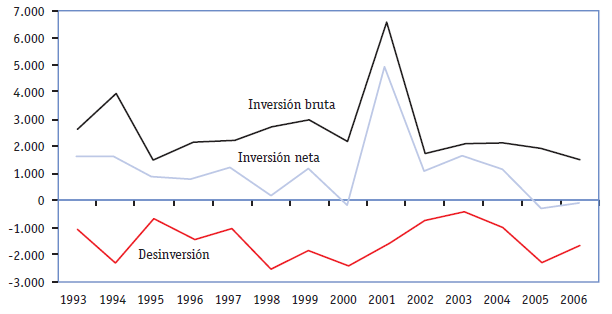

Many studies are linking foreign direct investment (FDI) flows with offshoring. If we look at the data for our country, there has been a great boom since 1985 that is due to a global structural change linked to the liberalization of the markets, which generated a growing rivalry between companies, as well as the development of emerging economies and the facilities for greater fragmentation of production provided by ICTs.

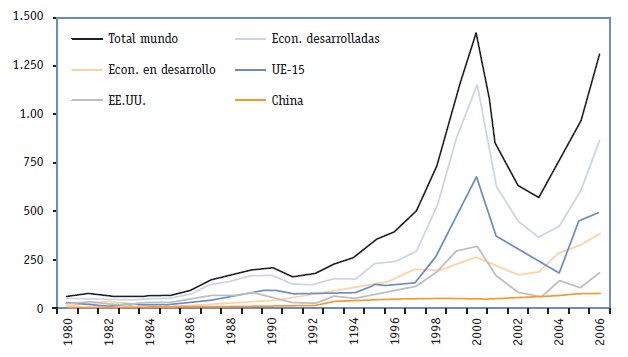

Although its priority destination continues to be developed countries, as can be seen in the following graph, it has gradually been directed towards less developed areas, where almost half of the world stock of FDI is already accumulated.

This position of emerging economies as recipients of investment is accompanied by a rapid rise in their manufacturing exports.

Flows of foreign direct investment received, 1980-2006 (billions of dollars)

Since joining the EU, there have been two different stages. Between 1986 and 1996, Spain was a net recipient of capital and it is from 1997 when it becomes an exporter. Although these capital flows, mainly to the EU and Latin American countries, are fundamentally destined for the services sector, it is the industrial sector that suffers the most from the effects on the volume of employment.

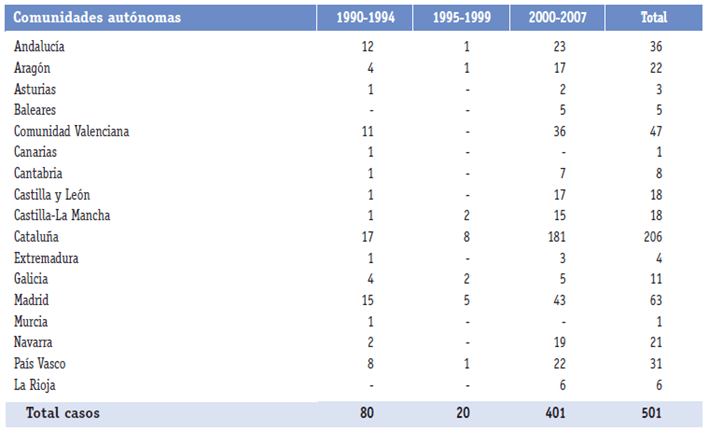

Relocation of industrial companies in Spain, 1990-2007 (number of operations)

The table above shows how a first wave of relocations took place in the first half of the 1990s as a result of joining the European Union and it is the second wave, towards emerging countries, that has brought attention due to its volume of operations and great media effect.

As expected, most of the relocations (41%) have been carried out in Catalonia, which is the largest Spanish industrial hub.

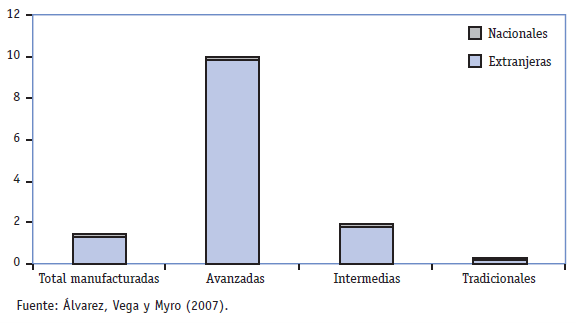

Relocation of companies in Spain, 2000-2005 (percentage of employment destroyed over that existing in the year 2000)

We see in the table above that the effect has been much more important on advanced manufacturing, where the presence of subsidiaries of multinational companies (MNCs) is more common. This also makes it difficult to ever have a powerful Spanish high-tech industry.

Of the total jobs lost due to relocations, 84% have been in foreign MNEs (84%), which highlights the dependence of the Spanish industrial fabric and its occupation of these corporations.

Offshoring of companies in Spain, 2000-2005 (percentage of employment destroyed over that existing in the year 2000)

One comment remains on investment flows and that is that, although the outlook is not encouraging for the future since the very maturity of the production system has been reducing business opportunities, it is true that this profile does not differ much from that of other countries community where the FDI of manufactures has been losing positions to services.

On the other hand, the Spanish FDI abroad has grown notably from what can be deduced that the surviving companies seem to have assumed a growing internationalization.

Bibliography

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. España en cifras 2021.

- Rowan Moore Gerety (2021). Deslocalización y rentabilidad privada. MIT Technology Review.

- José Ramón Fernández de la Cigoña (2021). ¿Relocalización? Nueva tendencia de moda en muchos de los sectores industriales. Sage Advice.

- Rosemary Coates, Alex Levy, Daisie Hobson, Jasmine Afshar, (2019). Survey of global manufacturing. The changing trends of reshoring in the United States. Reshoring Institute.

- Dirección General de Política de la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa (2018). Globalización y deslocalización. Importancia y efectos para la industria española.

- Cámara de Comercio de España (2018). Mapa del sector industrial español: claves y retos.

- Boston Consulting Group (2015). Reshoring of manufacturing to the US gains momentum.

- Deloitte (2015). Propuestas para la reindustrialización de España.

- Comisión Europea (2014). Por un renacimiento industrial europeo.

- Harold L. Sirkin, Justin Rose, Michael Zinser (2012). How shifting global economics are creating an American comeback. The Boston Consulting Group.

- Esmeralda Linares Navarro (2009). La deslocalización industrial en Europa. Analistas económicos de Andalucía.

Further information

For any query or request for additional information about our services and technologies, please complete the following form: