Purpose of Water hammer analysis

One of the main purposes of water hammer analysis is to determine surge pressure or maximum expected pressure during transient conditions. This is of particular interest to evaluate operative scenarios: When a pump is suddenly stopped, a valve is closed, or any other scenario that implies a relevant change of flow rate, and therefore velocity in the pipeline.

In the previously mentioned scenarios, kinetic energy is converted into pressure, the pressure increase can be estimated in simple arrangements with the following equation:

![]()

(instantaneous operations)

This is the Allievi–Joukowsky’s formula. Where c = is the wave celerity, Vo = velocity, ρ = density.

Should a Water hammer analysis always be executed?

The question is always evident: should we execute this analysis always? The answer is not so straight forward. Leaving aside the length of the pipeline, normally what we look at is the velocity of the fluid, and if this velocity follows the typical design recommendation (e.g.: 3 mt/sec), you should not have any problem regarding surge. Remember that this applies to incompressible fluid, and simple topologies arrangements.

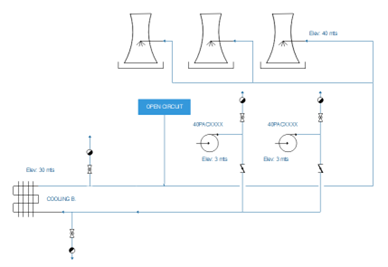

In the previous section it was indicated that the pressure increase depends on the velocity, but in every situation is obvious what is the resulting velocity after a change. For example, when you have an elevated section, and the flow is stopped suddenly after a pump trip and the systems experience a reverse flow condition:

During such conditions, literature offers you a series of possible engineering assumptions (see AWWA recommended technical papers, for example), but often you will have to rely on dynamic simulations.

High velocities and Design practices

High velocities could be present in systems like: Water cooling systems, crude export systems, and fire water supply systems, just to give typical examples. Following recommendations on design practices would give you a safeguard in front of these situations (Recommended closure time for valves, maximum velocity, among others). Proprietor design practices, AWWA manuals, normally cover these cases for power plants, but conditions could be special, and you will have to identify as designer the situation or case scenarios that need deeper understanding or analysis. This often is the result of experience, but could also be identified by a preliminary analysis, or by an established common practice in the community or company where you work (yes! shared knowledge is important).

Conclusions about Water hammer and Transient simulation

In conclusion we can draw the following: first always check and validate your assumptions, then consult any design practice available regarding the matter, and finally if you have any doubts, you always can check for yourself. This last point is not always simple, because hand calculations are limited to simple topologies, so when you have a complicated network, with many branches and components, you will need specialized software or a spreadsheet to help you with the iterative process.

References to such procedures are elsewhere like S. Manbretti (2014), Laredo Robinson (2022), Bryan W. Karney (1990). Some companies even have invested in their own software package but consider: there are plenty of choices in the market available to proceed with your analysis.

Final recommendations for Piping stress analysis

Always be aware of the design code that you are using, for example ASME code permits allowances in the maximum operating pressure as long the frequency is below 100 hrs/year (ASME B.313, sub section 302.2.4).

In the case of AWWA, there is a paper called: “Committee Report: Getting Started in Transient Analysis” which can help you to get the basics on this topic for water systems.

These are our recommendations for you, if it is your first time facing these kinds of doubts, or if you are a starting practitioner in this field.